Last November, we kicked off a research project on the emerging category of AI Interviewers here at Kyle&Co. The work culminated in a new type of research for Kyle & Co: A Category Compass, meant to bring clarity and guidance into the confusion of emerging product categories.

As we all know, AI is allowing product teams to build faster than ever, which means new categories and products will be entering the market at a faster pace than ever before, bringing additional complexities to an already complex market.

Well, working on the AI Interviewer Category Compass in particular was personal for me in a way most research projects aren’t.

Before analyzing this market, I had been closely involved – at a product strategy level – in helping build an AI interviewer myself. In addition to giving me a strong foundational understanding of the category going into this, that experience also gave me strong instincts about what mattered, what was hard, and where I believed this category would ultimately land.

Our Category Compass project gave me a rare opportunity to pressure-test those instincts by looking under the hood of how 12 different product teams approached the exact same problem, and for the most part, at the same time.

I knew this wasn’t a typical product category. AI interviewers are still in the early innings of the innovation cycle, and from my perspective, this is the first category I’ve seen emerge before any incumbent defined the path forward.

Broadly, TA Tech vendors are all chasing the same broad goal – use AI to automate candidate interviews – but there’s no established blueprint, no shared sense of “this is how it’s done.” Instead, we are watching a category take shape in real time, with teams making foundational product decisions independently, guided by very different philosophies and choosing very different lanes.

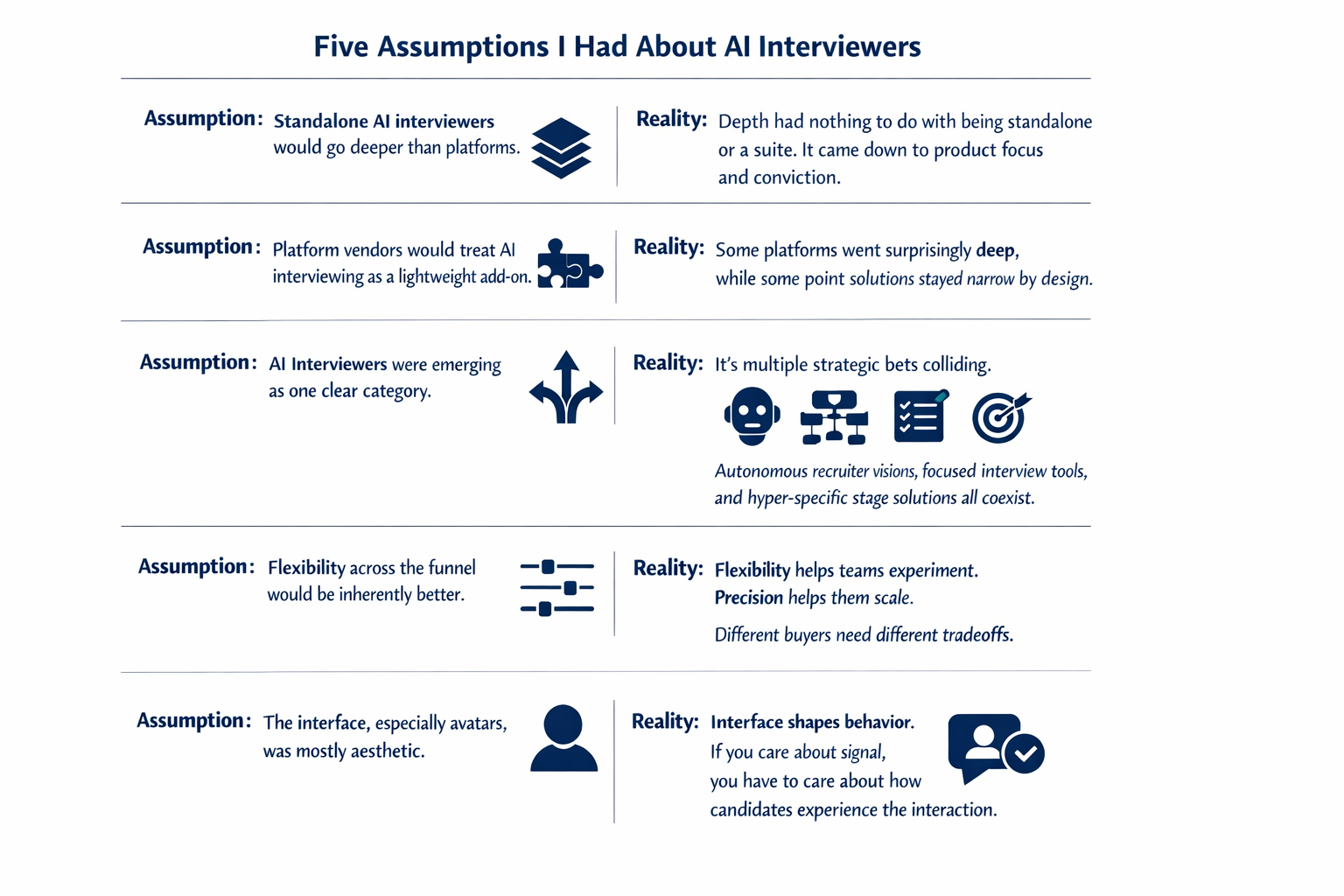

The Assumptions I Brought In (And Where They Fell Apart)

I went into this project with a few strong assumptions. The biggest one was structural: I expected standalone AI interviewers to go deeper and be more feature-rich, while the existing platforms who decided to add an AI interviewer to their product suite go less deep, as they have many other products competing for attention and resources.

That assumption didn’t fully hold up as I scrutinized solutions in both camps.

Yes, some platforms treated the interviewer as one feature among many. But there were also standalone solutions that went impressively deep, made thoughtful tradeoffs, and clearly understood the problem they were trying to solve. Depth wasn’t dictated by whether a company was a point solution or a platform. It was dictated by focus, product conviction, and clarity about what the interviewer was—and just as importantly, what it wasn’t.

That realization reframed the entire category for me. This wasn’t about what type of vendor was building the tool. It was about the product philosophy that drove them.

Here are the top 5 things I was wrong about

This Isn’t One Category – It’s Multiple Strategies Colliding

One of the hardest things to explain about AI interviewers is that they all look similar at a distance. Scratch the surface, and they’re fundamentally different products.

Some teams are clearly building toward an autonomous recruiter. For them, the interviewer is a strategic starting point – a wedge into a much larger vision of automating large portions of the recruiting workflow over time. The interviewer isn’t the destination; it’s the first step.

Other teams are very intentional about staying in their lane. They see enormous value in being an AI interviewer, full stop. They’ll add peripheral capabilities like scheduling or notifications when needed, but only insofar as it supports the core interview experience. Their differentiation comes from depth, not breadth.

Then there are teams that go even narrower. They take a strong stance on where in the hiring process their solution belongs and optimize relentlessly for that moment. These products aren’t trying to be flexible or universal. They’re trying to be excellent at a specific job.

These aren’t minor differences. They’re first-order strategic bets.

Flexible vs. Purpose-Built Interviewers

One of the clearest fault lines in the category is flexibility versus precision.

Some AI interviewers are designed to be inserted almost anywhere in the funnel. They can be used at the application stage, after an initial screen, or later in the process. This flexibility is appealing, especially to teams that are still figuring out what their ideal hiring workflow should look like.

Others are purpose-built. They’re designed for a specific stage – often the application phase – and they do that job extremely well. The signal is tighter, the experience more consistent, and the expectations clearer.

Neither approach is inherently better. But they solve different problems: Flexibility helps buyers experiment; Precision helps buyers scale. The challenge is that many buyers don’t yet know which one they need.

Standalone vs. Platform: The Real Tradeoffs

It’s tempting to frame this as a battle between standalone solutions and platforms, but that framing misses the point. The real story is about tradeoffs a buyer must consider.

Standalone approaches tend to move faster. They can take sharper product bets, iterate quickly, and go deep on the interview experience itself. They’re often willing to make strong assumptions about how interviews should work and design accordingly.

Platform approaches benefit from workflow context and data gravity. They fit more naturally into existing systems, inherit distribution, and can connect interview data to downstream processes more easily. But they also have to balance the interviewer against many other priorities.

Neither approach is “right.” But buyers should understand what they’re buying into. You’re not just choosing a product – you’re choosing a philosophy about how interviews fit into your broader hiring system.

The Interface Question: Avatar or No Avatar

One of the most interesting debates in the category is the interface itself, particularly around avatars. Everyone has a stance. Everyone has some data to back their stance. And everyone is still early.

I heard more than one team say they wanted to measure things like enthusiasm. That sounds reasonable on the surface, but it raises a deeper question: what’s the right interface to elicit enthusiasm when the candidate knows they’re talking to a robot?

This is where the category feels most unsettled. Some teams deliberately avoid anything human-like, prioritizing clarity and efficiency. Others lean into realism, believing that presence and familiarity matter, even if the interviewer is AI.

My take is measured but directional:

Over time, I expect the market will converge toward more human-like interfaces – including avatars – in scenarios where emotional engagement and realism matter. Not because they’re perfect, but because they reduce cognitive dissonance.

When the interaction feels more natural, candidates behave more naturally. That matters if you’re trying to understand how someone communicates, reacts, or engages under real-world conditions.

The Buyer Reality: Clear Problem, Fuzzy Mental Model

What makes this category especially complex is the buyer perspective. Buyers are very clear on the problem they want to solve: they want to automate interviews. They want speed, consistency, and scalability.

What they don’t yet have is a strong mental model for what the solution should look like.

How many stages should be automated? How autonomous is acceptable? What role should humans play in decision-making? What even constitutes “good signal” from an AI-led interview?

Buyers are learning the category while evaluating it. That’s why requirements shift mid-process. That’s why the same demo can land very differently with different stakeholders. And that’s why this market can feel noisy or confusing from the outside.

What Evaluating This Category Ultimately Revealed

Stepping back, the biggest lesson for me is that early differentiation in this category isn’t a bug – it’s a feature. We’re watching teams experiment with fundamentally different answers to the same question, at a time when both the technology and buyer expectations are still forming.

The long-term winners won’t just have better AI. They’ll have clearer opinions about trust, accountability, and where humans should remain firmly in control. They’ll understand not just how to automate interviews, but why and when automation actually helps.

I Guess I’m an Analyst Now?

AI interviewers are forcing the industry to confront something we don’t always like to admit: technology can move faster than our mental models for using it well.

This category isn’t just about automating interviews, it’s about deciding what we’re comfortable delegating, what we still want humans to own, and how much judgment we’re willing to encode into systems.

The teams that get this right won’t win because they automated the most. They’ll win because they made the most deliberate choices in a moment when there was no obvious path to follow.

And that, more than any feature or model, is what will ultimately define this category.